Sep, 30, 2008

Vineyard Gazette

Hockney, Van Gogh, Meet Marcia Smilack

written by Holly Nadler

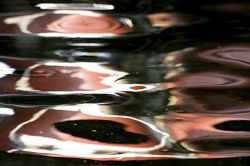

"Telephone Ring," an image that brings to the artist’s mind can can dancers.

There are landmarks in an artist’s career. First there’s the

initial sale of a piece of work. Then comes inclusion in a group show

and, with any luck (and, of course, talent), the solo show. But the

crowning glory arrives — often, alas, posthumously — when the artist’s

work is presented in the hallowed halls of a museum.

For West Tisbury photographer Marcia Smilack, who is very much alive

and kicking, and relatively young, the museum part of the trajectory

has arrived ahead of schedule. As we speak, she is on her way to

McMaster University Museum in Hamilton, Ontario, to visit her work

alongside paintings by David Hockney, Vincent Van Gogh and Wassily

Kandinsky, to name a few.

The exhibit, running through Nov. 15, is entitled Art And The Mind, and

it marks the first event, according to curator Greta Berman of

Juilliard’s Liberal Arts faculty, “to place genuinely synesthetic

artists in context and examine shared characteristics in their art.”

Synesthesia, which appears to lodge in the brains of many artists,

writers and musicians, describes an involuntary joining of the senses.

Synesthetes, in childhood, tend to think everyone hears colors, or

perceives letters in different hues, or imbibes various textures in

musical notes. When they learn about the rarity of their experience

(scientists calculate that one out of 100 people are synesthetic), they

generally stop talking about it. Recent interest and research in the

field should lead budding synesthetes to feel more comfortable with

their gifts.

Ms. Smilack explains, “We’ve been able to identify long-ago synesthetes

only by chance comments or anecdotes. For instance, Vincent Van Gogh,

when he was a kid, was ‘fired’ by his piano teacher because all young

Vincent wanted to talk about was the colors of the notes.”

The art exhibit at McMaster joins forces with the university’s

neuroscience department to shed light on assumptions about art and the

brain. It involves a conference, Synesthetic Relationship To Art; Ms.

Smilack, who will be addressing the crowds, has retitled it, What Does

A Metaphor Look Like?

"Music and Wood," by photographer who hears with her eyes.

This Vineyard artist began life in Columbus, Ohio, migrated to Brown

University, received a Ph.D. in English, taught at Boston College and

wrote articles for the Boston Globe. During the summers of the 1980s,

she rented Marijane and Matthew Poole’s cottage overlooking Menemsha

harbor. In honor of the dazzling view, she bought a camera.

“I didn’t know what I was doing, but every night I photographed the

sunset — same scene, different light and colors. I taped them to a wall

with an overall impression that sunsets are very symphonic.”

She was soon to discover that music attended every photographic shoot.

“One evening as I walked by a pond, I heard bagpipe music. It appeared

to emanate from a reflection on the water. The volume wasn’t loud, but

I could see it and simultaneously hear it, and that was the moment that

I clicked the camera.”

On another occasion, as she studied a pond shining like molten gold,

she distinctly heard cello music. She backed up, the music ceased, then

she tried again to walk into the moment. Again the quality of light

combined with the notes of a cello. Again she clicked her camera.

That some magical synthesis is taking place can be seen in Ms.

Smilack’s work: More than mirror images in water, they are, first and

foremost, arrestingly beautiful, but also weird and provocative, as if

fragments from an unfathomable but strangely stirring dream have

followed us into waking life. And as subjective and even supernatural

as the experience of synesthesia may sound to non-synesthetes,

neuroscientists have located that part of the brain that conjoins

senses when it lights up in MRI tests.

Meanwhile, when Ms. Smilack’s reflectionist photographs began to

receive an enthusiastic response from art dealers — and buyers! — a

coincidentally nascent interest in synesthesia brought the artist to

the attention of researchers and vice versa. “Twenty years ago,” she

relates with a laugh, “I first heard of synesthesia, but turned away

from it when I found it in the dictionary between seizures and

syphilis. Then in 1999 I picked up a New York Times piece and read an

interview with Carol Steen [also represented in the McMaster exhibit],

a synesthete and artist in New York city. She put into words what I had

known but had never said to anyone, not even to myself. The article

included her e-mail address. I sent a message with the header, ‘I hear

with my eyes.’ She answered right away, ‘Welcome to the club, you’re in

great company.’”

This new interest in the field has led to invitations for Ms. Smilack

to show her art — and to lecture about her modus operandi for achieving

that art — around the country, in Europe and now, in Canada.

When Ms. Smilack first crosses the threshold of the museum gallery

hosting the event, she’ll see three Hockneys ahead of her. As she

swivels her head to the left, she’ll take in several Kandinskys and

five Smilacks. What a rush! Also included in the exhibit, in addition

to those already mentioned, are artists Joan Mitchell, Charles

Burchfield and Tom Thomson. In keeping with the dead artists tradition

of museum shows, only three out of the seven contributors are among the

living.

Ms. Smilack calls this "Kandinsky-ish".

McMaster’s curators anticipate the exhibition will bring about a

new and intense kind of visual thinking. They also hope to reach beyond

the bodies that will gather in the physical plant by producing a

catalogue with essays by six scholars and the inclusion of lush

photographs. Curator Berman writes, “The catalogue will ensure that the

scholarship will be accessible to many who can’t attend, as well as

providing a lasting record of the research involved.”

Meanwhile those interested in a preview of Ms. Smilack’s work can go online to marciasmilack.com.