Jan, 16, 2007

Connecticut Post

The Sound of Photos

written by Brandie Jefferson

The Sound of Photos:

Artist shares her unique perception in Ridgefield photo exhibition

By Brandie M. Jefferson Associated Press

When Marcia Smilack goes down to the water near her home in West

Tisbury, Mass., to take photographs, it's important that there's

nothing on her mind. She looks straight ahead, walking along a pier on

Martha's Vineyard, until something in her peripheral vision also

stimulates her other senses. When she sees something, she also hears it

as, for example, chimes.

That's when she hits the shutter.

It may sound poetic, but taking a picture of the sound of chimes is

more than a metaphor for Smilack. She has a rare neurological condition

that makes it possible for her to take a picture such as "Furry Lights

and Chimes" that she feels and hears as well as sees.

It has led her to document life on Martha's Vineyard in photographs that only she perceives wholly, yet have a universal appeal.

The 57-year-old Columbus, Ohio, native is one of an unknown number of

people that have synesthesia — from the Greek words "syn" meaning union

and "aesthesis" meaning sensation.

Anina Rich, a researcher at Harvard's Visual Attention Laboratory who

did her doctoral thesis on synesthesia, said synesthetes

(sin-ess-TEETS) most commonly see letters and numbers in distinct

colors: 'A' is always red, for example, or '3' is brown, no matter what

color ink the characters are printed in.

Less common is linking several senses at once, as Smilack does. Her art

provides a sideways glance into a different way of perception.

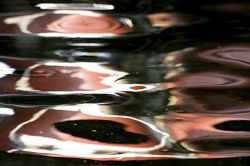

Smilack says her photograph that best represents synesthesia is "Fish

in the Sky." Like all of her pictures, it's a reflection on the surface

of water. A boat is gently distorted on a partially cloudy day. To the

left of the mast, faintly visible behind the clouds, is a fish that was

swimming close to the surface when she caught the image.

Focus on the boat, and the fish is nearly impossible to see. Focus on

the fish, and the boat — which takes up most of the shot — somehow

becomes a peripheral image.

"The difference in making the fish the focus versus the boat is what

synesthesia feels like," Smilack said. Her secondary perceptions are

always available to her, but typically they don't take center stage.

Smilack has no formal photography training, she moved to the island

after she finished her doctoral degree in English literature. She had

been working on a book, but found herself distracted by the buoys

outside her window.

"The light hitting the buoys struck like a siren for me," she said, and

she decided to photograph them. "I just couldn't resist. I never

finished the book."

She currently has an exhibit at The Enchanted Garden Conservatory of

Arts in Ridgefield, Conn., where a six-foot print of "Fish in the Sky"

is on display. And a Japanese film crew visited the Martha's Vineyard

to include Smilack in a two-hour television documentary that aired at

the end of last year.

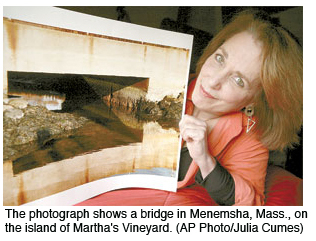

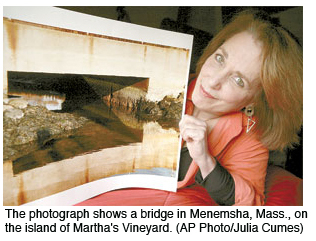

Most of her photographs are reflections of large, rigid structures —

boats, bridges, cityscapes — taken on the surface of calm waters. In

some cases, the distorted effect is indistinguishable from broad

paintbrush strokes.

"On water, things look much more like the way things feel," Smilack

said, glancing sideways. Any given image exists just for a moment.

Viewed from a different angle, it disappears.

When she drives down the winding street in West Tisbury that leads to

her house, Smilack sees more than the road ahead. Hovering somewhere

between her left peripheral vision and the outside world, shapes morph

in and out of each other, dancing in three dimensions. But if she tries

to look directly at them, she said — poof! — they're gone.

"I'm watching the sound of my voice, the sound of the car," she

explained. But not to worry, she said assuredly, the shapes don't get

in the way.

Most people with synesthesia would never call it a disorder.

"That would implicate that there is some problem, some disability that

you are facing," said Sean Day, president of the American Synesthesia

Association and a friend of Smilack's.

"There can be unpleasant moments" — like the time he fell out of his

seat when the colors he saw after hearing a theremin, an electronic

musical instrument, caught him off guard. "But in general, it's not a

problem."

Synesthesia is such an integral part of her life, Smilack said — almost

banal — that it never came up with her immediate family. After all,

"would you ever talk about breathing?" she asked.

She is convinced that most people understand the synesthetic associations, even if they can't experience them.

"Why do people talk about sharp cheddar cheese or loud colors? What

ends up in the language expresses some fundamental truth about people,"

she said. "You know exactly what it means, but why?"

Smilack thinks there's something very basic about synesthesia. Maybe

her brain has vestigial connections that allow, for instance, visual

inputs to be processed as sounds.

One popular theory of the condition is that people with synesthesia

have extra neural connections in their brains that most people were

born with but lose over time. Another theory suggests most adults have

sufficient connections, but only certain people are able to use them.

Her perceptions don't distract her, Smilack said.

In fact, she thinks her world is more open and balanced than for people

without the condition. For most people, there is a brick wall between

consciousness and the information that hits the eyes or rattles the

ears, but doesn't quite make it to perception. The information is

available to her at all times, in the periphery of perception.

"Consciousness," she said, "is just a curtain for a synesthete."

This difference in perception has caught the attention of scientists

around the world who think that understanding the exceptions may help

explain the norm.

"It's a fascinating thing that happens to a minority of the

population," Rich said, but for the majority of people, still, "you're

talking, integrating the visual with the auditory input, all

effortlessly.

"How is it that we get this cohesive view of the world when we're processing in different parts of the brain?" Rich said.

In one study of 150 self-reported synesthetes, Rich and her co-authors

found that over three months, those who said they were synesthetic

reported the same color for a particular letter with an 87 percent

consistency. The control group had only 26 percent consistency after

just one month.

The study also used functional magnetic resonance imaging to monitor

blood flow in the brains of people who experience colored letters and

found they had unique activity in regions involved in processing visual

information when the control subjects did not.

Smilack has been in contact with researchers around the world. She has

been surprised by the parallels they find between her art and their

research, comparing, for instance, pictures of sounds to sine waves

created by vibrating strings.

One researcher asked Smilack if she was offended by his attempts to discuss her art in the cold, clinical terms of physiology.

Smilack, who is working with scientists to create visual aides for the

blind, and has made herself the subject of much questioning, said she

thinks it's all related.

"The physiological process," she said, "complements the art."