The extraordinary Synesthesia: Art and the Mind

exhibition at the McMaster Museum of Art highlights artists who are

known synesthetes (David Hockney, Joan Mitchell, Marcia Smilack, and

Carol Steen) and works by artists thought to be synesthetic (including

Charles Burchfield, Tom Thomson, Wassily Kandinsky, and Vincent van

Gogh). Presented in one room, with each artist’s contributions grouped

together, the exhibit both allows a visitor to focus on the unique

attributes of each artist and to see the overlapping dynamics among

them. Had the exhibition merely provided a rare opportunity to explore

the high-quality work synesthetic artists, it would have made a

tremendous contribution.

Fortunately, the co-curators, Carol Steen and

Greta Berman, went one step further and incorporated the historical

research of Heinrich Klüver’s (1897-1979) on “Form Constants” and

reproductions of artwork by several early twentieth century synesthetic

artists studied by another scientist, Georg Anschütz (1886 -1953). In

addition, and much to the credit of all involved, a catalog featuring

six scholars and several color reproductions accompanies the exhibition.

This book make Synesthesia: Art and the Mind available to those unable to attend and will provide historical documentation for later generations.

Synesthesia is an involuntary joining of senses in which the real

information of one sense is accompanied by a perception in another

sense. Older views that this form of perception was either abnormal or

metaphoric have been replaced with a growing understanding that, while

idiosyncratic, the synesthetic experience is quite real and more

pervasive than formerly thought.

Research that has confirmed the reality

of synesthesia has also led to a re-evaluation of the symbolic,

metaphoric and associative approaches to art that have long aimed at

weaving the rich and resonant relationship among the senses together.e.g., an opera or a

ballet, etc.). What this means is that synesthetes have a life-long,

seemingly automatic ability to combine sensory experiences that

accompanies all aspects of their lives. More specifically, we now know that the experiences of genuine, genetic

synesthetes are qualitatively different from the type of cross-modal

intensification we have when engaged with an approach to art that is

intended to stimulate multiple senses (

Research has confirmed these

combinations (e.g., color and sound, colors and letters, etc.)

and found that they are both involuntary and consistent over time. We

also know that about 5% of the population has one of approximately 54

kinds of synesthesia and that creative people are more likely to be

synesthetes (or at least to acknowledge their synesthesia).

Since cross-modality has many associations with art historically, the Synesthesia: Art and the Mind

exhibition offers a priceless opportunity to think about what artists

with synesthesia add to our understanding of art per se, how the brain

of an artist with synesthesia differs from that of a non-synesthete (and

from the brain of individuals of the general population), and how our

individual endowments are harnessed in creative pursuits. While this

review can hardly cover the impact of the McMaster show on my thinking, I

will attempt to capture its essence in some overly abbreviated thoughts

on the exhibition and the themes that accompanied it.

First, I was quite impressed by the display as a symphonic whole. For example, Carol Steen’s Runs off in Front, Gold,

2003, although off to the side of the entrance, was the first piece I

noticed upon entering the room. Somehow, its powerful statement

immediately brought out the quality of all of the work on display.

One

of the curators of this exhibition, Steen has had a major role in

bringing synesthetes together, educating the public about the reality of

the synesthetic experience, and highlighting how synesthesia can aid an

artist in capturing the ineffable. Steen is a visual artist who paints

the brilliantly colored images she sees when she listens to music. [Some

of it is available at http://www.synesthesia.info/slides/.]

Although

her abstract pieces are expressive and essentially indescribable,

suffice it to say that there is a freshness, fluidity, and musicality to

Steen’s work; she has said that she To oversimplify, the layering and

rhythm of the paint had an energy that is reminiscent of aspects of the

work of Jackson Pollack and Mark Rothko, who were not synesthetes, but

are known for the way their paintings often trigger complex sensory and

perceptual experiences for the viewer. What really stayed in my mind as I

observed Steen’s art, and what I wish I could convey in this review, is

how the strength of her work is simply lost in web reproductions and

publications.

The

placement of Steen’s artwork nicely played off of the abstractions in

Joan Mitchell’s paintings on the one side and the more figurative work

of the Canadian painter Tom Thompson on the other. The Runs off in Front, GoldBrown Bushes, Late Autumn (1914), a small oil on wood from the National Gallery of Canada

collection that has similar colors and energy. A largely self-taught

artist who began to paint seriously in his thirties, Thomson’s

figurative work contains a tension between abstraction and landscape

that also brings to mind Cézanne’s late paintings and watercolors, which

often dissolve into color geometries. In terms of synesthesia, there

was an uncanny resemblance between the Steen abstractions and the more

representational Thomson, who also brought to mind the way van Gogh’s

strokes added expressive elements to a figure or scene.

This reference

to van Gogh is not an arbitrary one as it is said that van Gogh maddened

his music teacher by stubbornly testing his ideas on tone-color

correspondences during piano lessons. This remark (and others) has led

some to say that van Gogh was a synesthete. To highlight the connection

between a van Gogh and synesthesia, a van Gogh from the McMaster

collection was included in the show next to the Thomson piece. piece,

for example, had an extremely close resonance with Tom Thomson’s

Second,

because each artist had several pieces grouped together, except van

Gogh who was represented with only one painting, the display permitted

the pieces to echo one another and allowed the viewer to easily see the

style and personality of each individual artist. I particularly

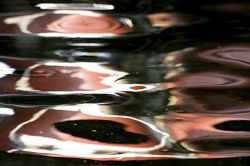

appreciated this arrangement when looking at Marcia Smilack’s five

pieces. Smilack, who calls herself a “Reflectionist,” photographs

reflections on water as she hears them. The tantalizing results have a

painterly quality that is unlike the work of any other artist I know.

Writing about one piece, “Kandinsky-ish,” Smilack says:

“I

watched the reflection on water until the pink turned to satin against

my skin. As I watched the concentric circles dilating as they formed and

reformed, I soon felt myself become one with the motion. Free of

thought, I felt myself become what I was looking at and clicked the

shutter. A few days later, I was in a store looking for an art postcard

when I came upon one that startled me and gave me a jolt of excitement,

for the painting looked just like my new image (to me).

I can only say

that my sensation of recognition was unmistakable and unshakeable and

remains so to this day. When I turned it over to find out who had

painted the image, I discovered it was Wassily Kandinsky. The painting

was “Squares with Concentric Circles.” My only question, then and now,

was whether Kandinsky had the same form of synesthesia that I have.”

Smilack’s

works were hung next to the three Kandinsky’s in the show and I was

drawn to the way the abstractness of his work seems more formally

developed than Smilack’s repertoire. Indeed, what I find most appealing

about Smilack’s work is her ability to mix abstraction with

representation and fluidity with form.

Thinking about her results,

(viewable at marciasmilack.com/),I am tempted to say that the

photo-paintings are so sensitively seasoned that they just taste right,

although I am not a synesthete. What my comment means is that the work

has the flavor of a properly prepared gourmet dish comprised of

ingredients that one might not be able to identify precisely, but whose

combination one will never forget.

Ironically, the painterly quality of

Smilack’s photographs brings David Hockney’s photocollages to mind

because the “look” of his photographs is painterly more than

photographic. The irony here is that three of Hockney’s pieces are also

on display at the museum. These pieces are representative of how he

created opera sets, using his synesthesic color/sounds to inform his

artwork.

Finally,

in sitting down to write this review, I found my enthusiasm for the

artwork was boundless and yet my “reviewer’s mind” kept returning to

some of the critical ideas that accompanied the show’s presentation,

Heinrich Klüver’s ideas about Form Constants in particular. At the risk

of trying to say too much in a limited space, I will nonetheless offer a

few thoughts on the historical ideas that were brought into the show.

Briefly,

early in the twentieth century, Klüver, a scientist, systematically

studied the effects of mescaline (peyote) on the subjective experiences

of its users. His investigations showed that the drug produced

hallucinations characterized by bright, highly saturated colors and

vivid imagery. In addition, Klüver found that mescaline produced

recurring geometric patterns in different users. He called these

patterns 'form constants' and categorized four types: lattices

(including honeycombs, checkerboards, and triangles), cobwebs, tunnels,

and spirals.

This work also pointed to what is now called a “geometry of

the mind” and is common to synesthesia, illusions, hallucinations,

migraine auras, ordinary perceptions, and can be seen in primitive art.

Richard Cytowic, a neuroscientist who studies synesthesia, has said that

Klüver showed that a limited number of perceptual frameworks appear to

be built into the nervous system and that these are probably part of our

genetic endowment.

Klüver’s

work with Form Constants was expanded in the 1970s by Jack Cowan and

others, who recognized that the kind of experience Klüver studied is not

just a trait we can associate with hallucinogenic experiences, but is

in fact a general property of brain structure, more specifically the

region known as the primary visual cortex or V1. Since many of the

recent studies I am acquainted with that look at color hearing seem to

use spoken words in testing subjects, and stress relationships between

colored hearing and cortical area V4, the introduction of form constants

in connection with synesthesia raised several (hard to articulate)

questions in my mind. A short review can hardly address my musings.

The

case a Jonathan I., the color-blind artist studied by Oliver Sacks and

others is among the few reported cases on individuals who have lost

their ability to see color but retain their ability to see form and

movement. What makes him relevant here is that he was both a painter and

a synesthete. Briefly, Jonathan I. lost his ability to see and even

imagine colors after a minor car accident. He also lost his

color-hearing synesthesia after his accident. Oliver Sacks’ diagnosis

was that Jonathan I. had cerebral achromatopsia, a loss of color

sensation throughout his entire visual field caused by damage to the

cerebral cortex.

Ronald Hoffman’s Visual Intelligence notes that

Louis Verrey 1854-1916, a Swiss ophthalmologist, discussed a patient

with a similar kind of neurological event in 1888. Verrey’s clinical and

postmortem observations of his patient found damage to the most

inferior part of the occipital lobe, in the lingual and fusiform gyri,

which are located near the primary visual area, V1.

Although no reliable

anatomical information is available on Jonathan I., John Harrison has

written (2001) that it is assumed Jonathan I., too, suffered damage to

the lingual and fusiform gyri of the brain. The larger point here is

that when Mr. I. his lost his ability to see color, he also lost his

color hearing synesthesia.

When

Verrey made his proposal, at the end of the 19th century, his

conclusions were hotly contested. Hoffman’s discussion points out that

the full implications of Verrey's work became clear in 1973 when the

neurologist Semir Zeki discovered the “color center,” the area in the

brain of the rhesus monkey that is specialized for seeing colors. When

this area is destroyed in the monkey or human brain, neither the monkey

nor the human can see colors. Based on this, color vision increasingly

was associated with V4.

At the time of Zeki's discovery

neurophysiologists were beginning to establish the outlines of a new

view of the visual cortex, suggesting that there are specific functional

units for seeing form, motion, and colors.[His work has also talked

about abstract art activating principally two areas of the visual cortex

of the brain (V1 and V4) and suggested that different schools of art

have their own neurological basis.]

Further research on synesthetic

artists might consider V1 to a greater degree, particularly in light of

recent tests that have found that have found if researchers stimulate

the lingual and fusiform gyri in human subjects by means of magnetic

fields, the subjects report seeing chromatophenes---colored phosphenes

in the form of rings and halos, much like some of historical work

included in this show.

Since Carol Steen has the kind of synesthesia

that evokes a perceptual experience within the mind’s eye (as compared

to a projective synesthete who would place the synesthete experience

within the world itself), her visual art, while clearly including a

visual component, is also a reflection of the images she sees in her

mind when she listens to music.These comments, while somewhat free form, bring to mind that the

relationship among form constancies, synesthesia, and creativity is a

complex one; as are the operations of the brain. I am drawn to ask

whether the linking of synesthesia with creative production informs the

brain in a way that both harnesses the synesthesia and reaches beyond

it.

Perhaps a kind of hypersensitivity inherent in the creative process

brings the synesthesia into the process in a way that might integrate it

with creativity and general and elevate other forms of visual

experience.

This kind of hypersensitivity hypothesis, I would think,

could also explain why artists who are not synesthetes, Paul Klee for

example, produced works that are sometimes coupled with synesthete

artists due to their stylistic components and cross-modal intentions.

Klee’s associative process offers a fascinating counterpoint because he

deliberately sought to bring a musical quality to his visual art, though

more in terms of its formal structure than its experiential roots.

Clearly, there is much to learn.Finally,

it is worth mentioning that this show is virtually unique in its focus

on synesthesia. Aside from the early twentieth century exhibitions that

accompanied the conferences organized by Georg Anschütz (in conjunction

with his publications of Farbe-Ton-Forschungen), I am unaware of

any shows that have focused on synesthesia per se. Indeed, shows

classified as such generally have failed to distinguish synesthetes from

non-synesthetes, mixing symbolic, associative, and metaphoric efforts

to convey cross-modal experience with work that may have been done by

synesthetes. These alternative shows, such as the 2005 Visual Music

exhibition, where the idea of synesthesia is used as an audience draw,

have failed to distinguish among genetic, associative, symbolic, and

metaphoric conceptions of synesthesia.

The curators of the popular Visual Music

show, in my view, missed an opportunity to educate the public about

what new research in synesthesia has revealed to us. The McMaster effort

does not make this mistake.Co-curated by Carol Steen, a synesthetic

artist, and Greta Berman, a professor of art history at The Juilliard

School and a researcher in this area, and coordinated by Prof. Daphne

Maurer, Department of Psychology, Neuroscience & Behavior at

McMaster University and Carol Podedworny, the Director of the McMaster

Museum of Art; this is an exceptional show. Unfortunately, the McMaster

show will not travel. The catalog, to some degree, allows scholars and

the public to continue to savor it after it closes.

Information about

the purchasing the catalog is available at:

http://www.mcmaster.ca/museum/exhibitions_publications.htm.